Ukrainian folk-dance legend no perfect hero

Shcho pravda — to ne hrikh, goes the Ukrainian proverb: [Saying] the truth is not a sin.

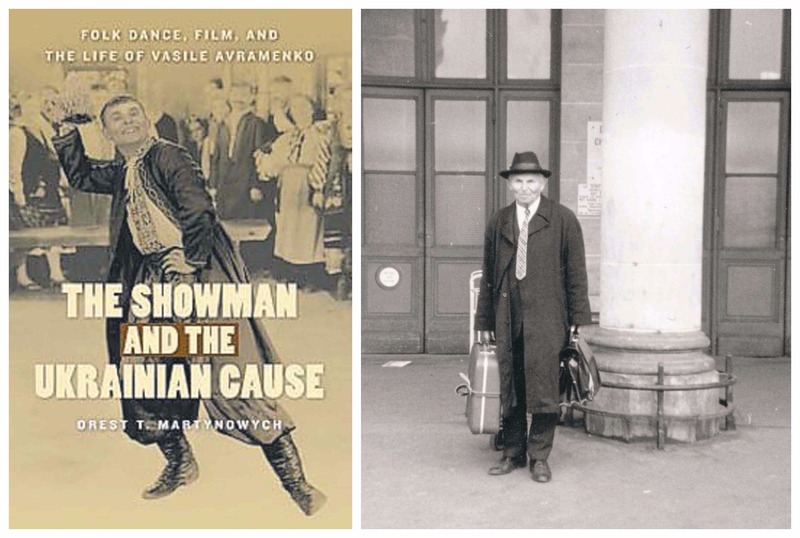

While giving Vasyl Avramenko credit for his many accomplishments, Orest Martynowych's book knocks a hero off his pedestal. Not so much knocks him down, but brings to light how Avramenko did it to himself.

Vasile (Vasyl) Avramenko (1895-1981) was a larger-than-life figure in the Ukrainian North American community from the late 1920s into the 1960s — a dancer and dance teacher, film producer, and impresario. It is because of him that Ukrainian folk dance grew on this continent into the phenomenon it is now. The founder of Rusalka, Peter Hladun, studied with Avramenko, as did so many other dancers and founders of other Ukrainian-Canadian dance ensembles.

Avramenko was known across North America. As a child in the 1950s, this reviewer remembers taking the Hudson Tubes train with my parents to Manhattan from New Jersey to see Avramenko's films in a hall on the then Lower East Side (now the East Village).

Martynovych is a historian at the Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies at the University of Manitoba, and is the author of Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Years, 1891-1924. He is meticulous and scrupulous in his research, much to the chagrin of those who remember only the legend of Avramenko.

The book covers Ukrainian, Ukrainian-Canadian and Ukrainian-American history, culture, politics, and entertainment over many decades; it's well-illustrated with archival photographs. However, in today's world, transliteration from Ukrainian rather than Russian should be used, e.g., Dnipro River (not Dnieper).

Born in the Kyiv region of Ukraine (then part of the Russian tsarist empire) in 1895, Avramenko had a difficult childhood under a cruel father. As a teenager he travelled for work to Vladivostok. It was there he saw his first theatre production, the Ukrainian operetta Natalka Poltavka. This inspired Avramenko's passion for theatre and productions, and he never looked back.

This biography is an engrossing journey of self-discovery, learning, enthusiasm, patriotism, world travel, accomplishment and loneliness and disappointments.

Martynovych writes that "modesty and perspicacity were not the maestro's (as he liked to be called) strongest traits. Convinced that his work was more important than any other Ukrainian in North America, Avramenko amassed and guarded an enormous archive of more than 150 large boxes of documents."

No one can take away from Avramenko his endeavours and legacy in Ukrainian folk dance, film production and popular culture. But his fundraising and investment methods tainted that legacy and ruined his reputation among his investors. Some artists have no business notion at all, although some misadventures are not of their deliberate doing. Martynowych explores both sides of the man and his character, providing exact details on every page of this fascinating book.

The Showman and the Ukrainian Cause will be of interest to many Manitobans, including those who learned Ukrainian dancing from Avramenko or from his original students, those who performed in his films, and those who lost their money through investing in his projects.

Winnipeggers now retired still remember dancing in the mass "Metelytsia" dance choreographed by Avramenko at the Winnipeg Arena during the celebrations in 1961, when the Taras Shevchenko monument at the Manitoba legislature was unveiled by John Diefenbaker.

Many Winnipeggers are mentioned in the book, including Senator Paul Yuzyk, Slaw Rebchuk, Ivan Bodrug, Meros Lechow, Wasyl Swystun, Steve Juba and Alexander Koshetz.

In great detail, Martynovych "attempts to present a nuanced and balanced picture of a deeply flawed but fascinating character, one who deserves a place in the history of interwar Canada and North American popular culture."

Some readers who remember Avramenko may question why Martynowych "tarnishes" the reputation of a great man.

But the author simply presents the truths of a well-documented life — the readers can decide. Now we know about the whole person, not just the persona.

Comments