Holodomor: How a female Jewish journalist alerted the world to Ukraine’s silent starvation

While driving through the Ukrainian countryside in 1932, Rhea Clyman, a Jewish-Canadian journalist, stopped in a village to ask where she could buy some milk and eggs.

The villagers couldn’t understand her, but someone went off and came back with a crippled 14-year-old boy, who slowly made his way to her.

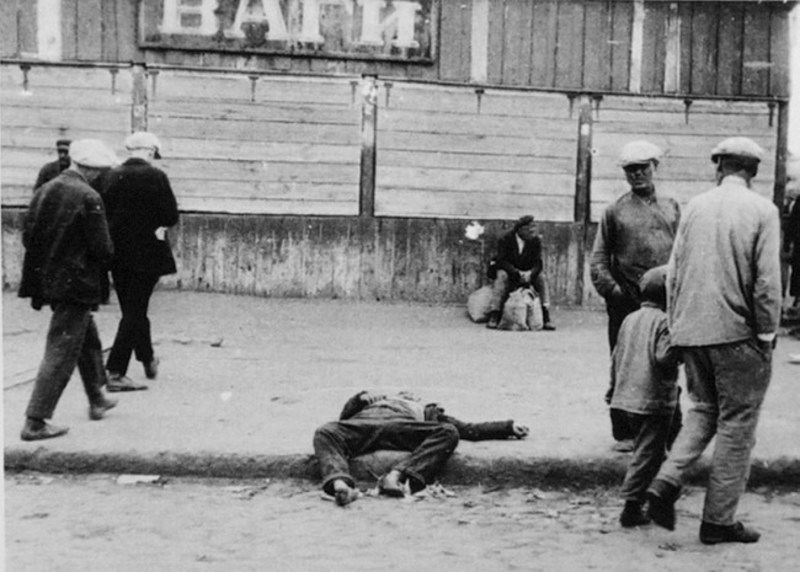

“We are starving, we have no bread,” he said, and went on to describe the dire conditions of the previous spring. “The children were eating grass… they were down on all fours like animals… There was nothing else for them.”

To illustrate the point, a peasant woman began to peel off her children’s clothes.

“She undressed them one by one, prodded their sagging bellies, pointed to their spindly legs, ran her hand up and down their tortured, misshapen, twisted little bodies to make me understand that this was real famine,” recalled Clyman in a piece published by the Toronto Telegram, one of the largest Canadian newspapers at the time.

Largely forgotten, a Ukrainian professor in Canada is writing a book about Clyman, the first-ever biography of the intrepid reporter.

“She went to the Soviet Union feeling very optimistic, [expecting that there would be] no unemployment, that men and women were equal,” said Jaroslaw Balan, of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta. “But she very quickly came to the realization that this was an incredible totalitarian state — how poor people were and how difficult their lives were.”

Clyman was born in 1904 in Poland, then a part of the Russian Empire, and immigrated to Canada when she was 2 years old. At the age of 6, she was hit by a streetcar and had her leg amputated. She spent the next few years in and out of hospitals.

Yet this didn’t stop her, at age 24, from traveling alone to the Soviet Union and trying to make a living as a freelance foreign correspondent.

In 1928 Clyman got off the train in Moscow with no acquaintances and only a few words of Russian. She spent hours in the train station until someone showed her the way to a hotel, where she slept in the bathtub of an American journalist. She was to remain in the Soviet Union for the next four years.

“A lot of newspapers sent journalists [to the USSR] for short [stints],” Balan said. “But she learned the language. She developed a perspective that was very different.”

At one point, Clyman traveled to Russia’s far north to the town of Kem, near a Soviet prison camp, a place off-limits to foreigners. She met the wives of the prisoners, saw the former inmates who were not permitted to leave the town even after they were freed, and reported on how the Soviets used political prisoners as forced laborers to chop wood. This was an important story for Canada, which was then losing its lumber market in the United Kingdom to the cheaper Soviet competitor.

“It supported the claims that cheap labor was used in the Soviet Union, and [that’s why] Canada couldn’t compete,” Balan said.

But it was Clyman’s coverage of the Holodomor, the man-made famine estimated to have led to the deaths of some 4 million Ukrainians between 1932 and 1933, that really interests Balan. He first came across Clyman’s work while searching through Canadian newspapers for what was written about the famine in Ukraine.

In 1932, Clyman drove in a car southward from Moscow through Kharkiv — then the capital of Ukraine — to the Black Sea and on to Stalin’s birthplace in Georgia.

A group of villagers on a collective farm gathered around her to see if she could bring a petition to the Kremlin to tell the Soviet leaders that the people were starving. All their grain had been taken away. Their animals were long ago slaughtered. When she tried to buy eggs, a village woman looked at her incredulously and asked if she expected to get them for money.

“Of course,” Rhea answered. “I don’t expect to get them for nothing.”

“You don’t understand,” the peasant told her. “We don’t sell eggs or milk for money. We want bread. Have you any?”

Balan said that Clyman developed insights into the causes of the famine — that it was not just due to drought, but a result of forced collectivization. For instance, the Soviet attempt to mechanize agriculture led to problems when the production of machinery didn’t go as quickly as planned. Horses and cattle were already killed, but there weren’t enough tractors to harvest the crops. This was the result of poor decisions from the top, Balan said. When Ukrainians were starving, the Soviets sealed the borders between Ukraine and Russia so that people couldn’t escape, he added.

“Her story is important for Jews and Ukrainians,” Balan said. “Among Ukrainians, there are a lot of stereotypes that the Jews were Bolsheviks and that they were responsible for the famine. And here’s a Jewish woman who’s written about the famine. In truth, Jews were also persecuted. She’s Jewish too, but look, she wrote the truth.”

In 1932, Clyman became the first foreign journalist in 11 years to get kicked out of the Soviet Union, allegedly “for spreading lies.”

But from there she went to Germany, to report on the rise of the Nazis.

Balan still needs to do a lot more research to find the articles that Clyman authored from Germany. He said that he has only been able to read two of them so far.

Clyman reported from Germany until 1938, when fled the country on a small airplane together with a few Jewish refugees. Unfortunately, as the plane came in for landing in Amsterdam, it crashed. Nearly half of the passengers were killed and Clyman broke her back — though she somehow avoided paralysis.

She returned to North America, where she moved to New York and recorded her memoirs. She never married nor had children, and died in 1981.

Upon her death, Clyman’s memoir remained unpublished and Balan is hoping to find it. He is also trying to find out where she was buried. He located some of her relatives but they did not know where she was laid to rest, he said.

“If we could find her memoirs that would be an exciting thing to see, that would be a goldmine,” he said.

Balan recently gave a talk on Clyman at Limmud FSU in New York, the largest gathering of Russian-speaking Jews in North America. The talk was sponsored by the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter, a Canadian nonprofit that aims to promote cooperation between Ukrainians and Jews. Launched by Canadian businessman James Temerty, the initiative aims to do away with negative feelings between the two peoples.

“Jews have been living in Ukraine probably for 1,000 years, and certainly in large numbers since the 16th century,” Balan said. “If you take out the periods of the pogroms and the Holocaust, the rest of the time, Jews in many cases flourished in Ukraine.”

The two peoples have more in common than they might realize — the food, for one — and they should learn more about each other’s culture, said Natalia Feduschak, the director of communications for the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter.

Feduschak said that Clyman helps to bridge the gap between the two communities because she was a Jewish woman who wrote “about the Ukrainian famine with great compassion and great understanding.”

“Because of World War II and the horrific events of that period, the communities find it difficult to communicate with one another,” she said. “But there are a lot of similarities.”

Comments